According to David Chan Weng Cheong,

architecture is not just about designing a building. He tells FOONG PEK YEE

that it should also be about designing buildings that foster a loving and

lasting relationship among its inhabitants.

HENRY indulgently asked his three-year-old daughter, Angeline, whether

she would make milk for him when he was old.

“I don’t know where I will be living, daddy,” was her spontaneous reply.

The little girl’s response, which certainly wasn’t what the father had

expected, speaks volumes of the situation in contemporary society where

individualism is growing not only within the family but also in the

community.

The case in Singapore of an elderly woman whose skeleton was discovered

lying on the floor of her toilet a year after she died certainly underscores

the situation.

|

|

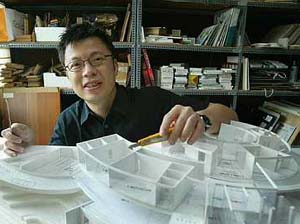

DESIGNER HOMES: Chan believes homes must be designed

with elements to accommodate extended families. — STARpic by SIA HONG

KIAU

|

Such real life stories are neither new nor uncommon and it is time to

address the issue collectively, said David Chan Weng Cheong, an architect

who is an advocate for building residential units that emphasise on family

bonding.

To begin with, he said, the design of any residential unit has a huge

impact on family bonding.

“This intricate relationship is a challenge to architects in modern

times,” he said.

“Architecture is not just about designing a building. It is the building

of a loving relationship among its inhabitants, one that could stand the

test of time,” added Chan, 43, who obtained his Bachelor in Architecture

from Curtin University, Australia in 1988.

Calling himself a “family activist”, he said homes must be houses with

designs conducive for nurturing family bonding.

“This can be as simple as planting a mango tree and plucking the fruits

together with your children,” he explained.

“This simple act of sharing over the years can form lasting images on

your children’s memory.”

Chan has a list of 120 questions to help guide his clients to reflect on

what their dream homes should be like.

To have more interaction with children, Chan’s advice is to have a bigger

family area for daily activities ranging from reading and using the computer

to watching television together. Bedrooms should be solely for sleeping, he

advised.

“Among the rich, some will opt for designs which can be extended in

stages to include suites or apartments to encourage their children to stay

on when they are adults or have families of their own,” said Chan, who has

designed almost 50 bungalows priced between RM1mil and RM22 mil per unit in

the Klang Valley in the last four years.

Talking passionately about his work during an interview recently, he

pointed out a double-storey bungalow in Nilai, Negri Sembilan, that he had

designed for seven co-owners who were also relatives.

All the residents have only their bedrooms to call their private space.

The living situation in the bungalow is similar in concept to that of an

“extended family” and the values it encapsulated were certainly invaluable,

Chan said.

This concept perhaps is worth exploring for single people or even couples

who fear the “empty nest syndrome” in their twilight years but are not ready

to move into retirement homes just yet.

Chan has his childhood experience to look back on for his resolve in

designing homes around family togetherness. Growing up in a small town in

the 70s, Chan said, he heard many stories of people from his home town

moving to Kuala Lumpur for better jobs.

His father, a photographer, and his mother, a hairstylist, operated a

small shop in Bentong, Pahang and customers always talked about the latest

happenings in town.

The lure of the city lights saw small town boys and girls leaving their

hometown in droves, recalled Chan, who heard the stories while helping his

parents in their shop.

As it turned out, he would himself also leave his hometown – to further

his education, first in Sekolah Sultan Haji Ahmad Shah in Kuantan (lower

secondary) and then at Taylor’s College, Kuala Lumpur (upper secondary

education). He was 13 when he first left, and having lived with his parents

and three siblings – a brother and two sisters – and relatives and friends

all the while, he felt very homesick in his new surroundings.

“Until today, I still feel homesick, especially during festive seasons,”

said Chan who is single.

His journey into the world of architecture was not by design, Chan

confessed. He did engineering for a year at the Swinburne Institute of

Technology upon arriving in Melbourne in 1982.

“I somehow kept working part-time instead of attending lectures,”

recalled Chan who failed his first year exams.

“I initially chose engineering because it was something a small town boy

could do to make his parents proud then.”

Chan later convinced his father to allow him to change to architecture,

saying that architects could control engineers.

“I also did not know much about architecture but it was a course that I

could enrol myself in,” he admitted.

Chan worked as an architect for two years in Australia after he

graduated. He returned to Malaysia in 1990.

He set up his architecture and interior design business in Damansara Jaya,

Selangor in 2002 with three staff.

“Our staff strength is now 45, and 60% of them are my former students,

including my business partner Chan Mun Inn,” said Chan who lectured on a

part-time basis at LimKokWing University College, Kuala Lumpur between 1994

and 2001.

The way he sees it, bonding is not confined to family only. It can also

be in the work environment, in how clients and friends relate with one

another.

“I will be happy to see my staff doing well in their career, including

setting up their own practice one day,” he said.

“Change happens all the while. What’s important is how one responds to

changes and moves on in life.”